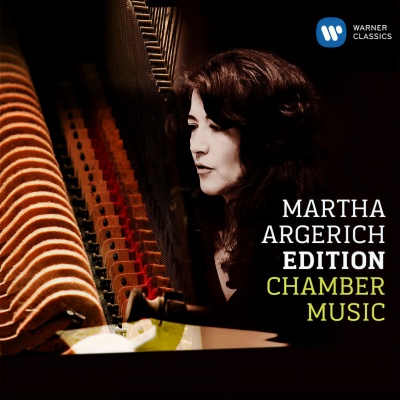

Martha Argerich Edition: Chamber Music

This 8 CD boxed set is another in a series to commemorate the art of Martha Argerich in her 70 th birthday year. How lucky we all are as music-lovers to have the chance - where we don’t already own them - of obtaining these fantastic performances by a true artist. The title of one of the articles in the accompanying booklet is “The spirit of collaboration”. That sums up this set, for Argerich has, for many years, eschewed solo performances in favour of the collaborative process where she shares the platform with a whole range of world class colleagues, some very well known and some less so. You can be sure that if she wants to play with them they are at the very top of their musical game. I recently reviewed her solo and duos set which I described as “an embarrassment of riches”; this is an even greater one: 8 CDs of performances of the works of 9 composers in which she is accompanied by a total of 23 different musicians! The choice of repertoire cannot be faulted, involves plenty of variety and shows Argerich as a perfect fellow musician whether in duos, trios, quartets, quintets or septet. CD 1 begins the journey with a performance of the Kreutzer sonata that is so good it is as if one were hearing it for the first time - as if a last jigsaw piece had been placed to complete the picture that had eluded you before but is finally revealed. These musicians are the music so excellence comes as standard. That is the overriding impression that one is left with at the end of the set; that Argerich has the ability to be the catalyst that enables the others to perform to their highest possible capacity. Together they produce performances that are superlative in every way and that helps the listener to reappraise every work they collaborate in and see them in a new revealing light. There is no doubt that live concerts almost always lead to the best performances; there is a saying that is oft repeated in the world of jazz that “the best jazz performances are never recorded” being live with no equipment on hand to capture the moment. It is lucky therefore that that is always the express intention at the festival in Lugano, Saratoga and everywhere Argerich is involved. With a couple of notable exceptions, in which she plays with Mischa Maisky at a recital recorded in a studio at the Conservatoire in Geneva, all the music here was recorded live. This produces such rapt attention that one is barely aware of any audience, until the deserved applause reminds us, and we are simply left with the results and benefits of live performances that are so exceptionally wonderful. I have reviewed several recordings of the Franck Sonata recently and remember how highly I praised the version with Shlomo Mintz and Yefim Bronfman so now I’m in a quandary; how does this compare? Well, I love them equally and wouldn’t want to be without either. If the two recordings were racehorses there would have to be a photo finish with a great deal of close examination with magnifying glasses - not in terms of timings as Argerich and Perlman are slightly faster and finish before Mintz and Bronfman in each movement - but if anything Argerich and Perlman find a soupcon of extra subtlety. I’ll have to leave it in the ear of the listener to hear whether they discern that too. CD 2 is of three Beethoven works and one of Chopin. It opens with Beethoven’s Piano Quartet Wo036 no.3 that is both pure genius and very well known. The performance is finely measured and full of panache, with an allegro finale that simply oozes the joy of four supreme musicians relishing the collective music-making experience. There’s an eruption from the audience at its close that underlines how this was communicated to them. Beethoven’s genius is, as they say these days “a given”; there is nothing to say about the music that has not been said and the same pertains to musicians such as those on these discs. Their “pedigree” is flawless and, satisfaction is virtually 100% guaranteed. So it is that we have another ravishing rendition in the shape of Beethoven’s Clarinet Trio with Marek Denemark’s clarinet sounding sumptuous alongside Mark Drobinsky’s gorgeously rich cello. Once again the trio’s finale comes with joyous playing which makes the most of Ludwig van’s innate ability to write a humorous and brilliant theme and variations that he manages to make sound so simple. Beethoven’s Piano Trio “Ghost” comes next with another fine performance. The name became attached to it - by others as is usual in such matters - due to the second movement which has an eerie sounding theme, perhaps influenced by the fact that Beethoven was contemplating writing some incidental music for Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” at the time. Argerich’s partners here join with her to emphasise the drama in the music to great effect and the presto finale comes as light relief. The disc is rounded off with Chopin’s Introduction and Polonaise brillante in C, op.3. This takes us into a different world in which romanticism has a far greater influence on the music than anything Beethoven ever wrote. It sounds almost light and, dare I say it, frivolous, after the cerebral works of Beethoven that preceded it. That is not meant in any way to sell it short; it is a great piece and is played here with the customary aplomb one naturally associates with artists such as Martha Argerich and Gautier Capuçon. Shrieks of delight from the audience confirm their assessment is the same. CD 3 concentrates of one of Argerich’s principal passions: Schumann, in four works that involve Argerich and one other musician. If there are any readers who have not yet succumbed to the captivating nature of Schumann’s music then this disc might very well be the touchstone of a sea-change in their thinking; it is a wondrous disc. The opening movement of the Violin Sonata no.1 in A minor, op.105 is achingly poignant and when you know of Schumann’s mental conflict you can hear it in every note. Her partner here is the young Swiss violinist Géza Hosszu-Legocky who, the booklet notes, is equally at home with jazz and gypsy music - his name is Hungarian so that comes as no surprise - and it is a wonderfully spirited performance as one might expect with a partner with that background. Next comes Schumann’s Violin Sonata no.2 in D minor, op.121 in which Argerich is partnered by Renaud Capuçon, clearly a particularly favoured colleague - he appears on no less than 10 works in this collection. It opens with a strongly stated theme in a movement that is lengthy by comparison with the others. Capuçon plays with real beauty that emphasises the pathos in the work. The playing throughout is really special and I especially enjoyed the third movement which is tinged with an almost palpable sadness yet with hope of better things to come. We are then treated to an exceptionally rare account of the transcription for flugelhorn of the Fantasiestücke op.73 with trumpet ace Sergei Nakariakov. It is hard to understand why we don’t hear this transcription more often; the flügelhorn which is an instrument that comes between bugle and trumpet is a far easier instrument to “tame” than a horn; whenever there are wrong notes to be heard in an orchestra the chances are that they come from the horn section. Once you get used to the fact that you are hearing a brass instrument rather than a cello the result is quite spellbinding. It is certainly one of Schumann’s sunnier works and this is a great version to have included in this set. The disc is completed by Märchenbilder op.113 with Nobuko Imai as violist. Every time I hear the viola I am reminded of the disparaging things said about it which I’ve never been able to understand - who could envisage doing without a viola in chamber music! - and this recording once again brings into focus what a wonderful instrument it is: rich and sonorous. I’ve rarely heard a viola sound so much like a cello as it does here, it is quite remarkable and the melancholic nature of the piece is declared right from the first movement in beautiful tones. Then, in the second movement comes the tune we all probably recognise best from this work with both piano and viola equally making a most powerful statement. The third movement is somewhat lighter in mood before the finale is reached which is marked Langsam, mit melancholischem Ausdruck: slow, with melancholic feeling. While the devil may not have all the best tunes I find more when the mood is sad and reflective than I do when it’s light and “gay”. This is a wonderful performance full of pathos and played with feeling and grace. CD 4 is another all Schumann one with three of his best known works in great performances. Argerich again exerts her uncanny ability to draw out the other musicians into producing some outstanding renditons of these works. Such is the obviously rapt attention given by the audiences that one has to remind oneself that these are live recordings and are all the better for being so. The Piano Quintet in E flat, op.44 is particularly fine and a perfect example of the collaborative process in action with all the musicians playing marvellously and exemplifying the very nature of an “ensemble” in which each member is totally “in tune” with the other in the most naturally musical of ways. The Piano Quartet in E flat, op.47 is no less wondrous with the brothers Capuçon teaming up again along with Lida Chen giving their all. This disc finishes with Schumann’s Andante and Variations in B flat, op.46 that has Alexandre Rabinovitch joining Martha Argerich on piano with Marie-Luise Neunecker on horn and two fabulous cellists, Natalia Gutman and Mischa Maisky who together produce a great end to a brilliant disc. More delights await us with CD 5 beginning with Haydn’s Gypsy Trio in a bright, airy and altogether delightful account that gives full vent to Haydn’s wit. It involves some pianism in the first movement that just has you shaking your head in admiration; the results are so crisp and precise. There is also wonderful playing from the Capuçons (again!) in the second movement where the violin carries the theme, and the third from which the trio derives its nickname. This again has you reacting with wonder as the violin and piano begin a headlong gallop with the Hungarian-inspired tune racing for the finish, interrupted only by some variations along the way. The deserved applause follows at the end of a fabulous superlatively played gem of a trio. The mood is decidedly different in the next item from the same three with Mendelssohn’s piano trio. I often wonder how one composer would have regarded the work of another who came after them. I thought of this again with this trio from a composer born the same year that Haydn died. Genius and generosity were embodied in equal measure in ‘Papa’ Haydn and I imagine he would have been hugely admiring of what Mendelssohn achieved. This trio is a perfect example of how the musical baton had been taken by someone from the next generation and further developed. I particularly love the “conversation” that the two strings appear to be having towards the close of the second movement. It is small wonder that Argerich chooses to play alongside the Capuçon brothers. They are simply brilliant and while they can produce heartfelt and world-weary sounds when required they can also embody their own youth when necessary: just listen to the third movement to hear what I mean. The final movement here is full of gorgeous - I’m fast running out of superlatives! - sounds that will have me returning to this work again very soon. It’s like a good book you want to re-read as soon as you finish it. Once again the audience’s reaction shows they had also experienced something very special. It’s back again to Schumann for the third work with the same trio this time tackling his Fantasiestücke op.88. The first two movements are in great contrast to each other, the first being extremely reflective whilst the second is light and happy, marked as it is Humoresque. For the most part Schumann’s markings leave the interpreters in no doubt as to mood so when we reach the third movement we have Duett: Langsam und mit Ausdruck (Slow and with feeling) which leaves the protagonists with the responsibility of interpreting the degree to which they should approach it. No problem there with these musicians who rise to the challenge with their usual aplomb and finesse. The finale is in march tempo. The last three offerings on this disc are from Debussy starting with his cello sonata with Mischa Maisky as partner. I have read many times how the French tend to undervalue their composers; can this really be the case? I adore Debussy I must say and as a Francophile find his music embodies so much of what I love about France. The cello sonata is a good example, being full of heartfelt emotion filtered through a gentle refinement. Debussy was writing at the same time as the impressionists were painting and perhaps he, more than most other French composers managed to “paint” his musical canvases: think of La Mer and Images, for example. The sonata is treated to a wonderful performance. The last two works are of Maisky’s arrangements of Debussy’s La plus que lente and Minstrels. These three Debussy works stand alone, apart from the César Franck that opens disc no.6, as being studio recordings. The date from December 1981 though they sound as fresh as if they’d been recorded this year. CD 6 opens with that studio recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata, as transcribed for cello. There are works that should be left in their original form: transcribing them does them no favours. I feel this, amongst others, especially when it comes to the Barshai arrangements of some of Shostakovich’s string quartets – even if the composer agreed to them. Renaming them “Chamber Symphonies” and appending an ‘a’ to the opus number makes no difference to me. Having got that off my chest I have to say that I do find this transcription more than acceptable. There is not such a huge difference in sound between violin and cello; at least they’re in the same ‘family’. Franck’s sonata is so ravishing it sounds quite at home in the realm of the cello. Maisky’s playing is highly effective; his cello almost sounds like a viola and, remarkably, he can play it as fast as a violin! The rest of the disc couldn’t be further from Franck’s sound-world or from that of the rest of the set as we now come to Bartók. Both Argerich and Renaud Capuçon show that they are at home playing “modern” works like these just as much as they are with music from the classical and romantic periods. The case for the Bartók sonata is cogently put by them in a powerful performance that is full of feeling. Contrasts is a wonderful and fascinating work for piano, violin and clarinet. It highlights Bartók’s love of folk-inspired melodies and Michael Collins’ beautifully ‘fat’ sound is perfect here against the thin and spiky nature of the violin writing. CD 7 continues with more 20th century works, this time including Shostakovich. I was very much looking forward to hearing one of my all-time favourite composers in the hands of Argerich and friends. I was not disappointed. In 1973 Shostakovich wrote: "Every piece of music is a form of personal expression for its creator ... If a work doesn’t express the composer’s own personal point of view, his own ideas, then it doesn’t, in my opinion, even deserve to be born." The private world of Shostakovich that he explored in his chamber works and in which he was able to express his innermost thoughts and feelings is immediately evoked at the outset in his piano quintet, op.57; his anxieties are almost palpable. It is obvious how well these musicians know the work which he managed to complete in a few weeks between summer 1940 and September that year. He gave the first performance in November 1940 with the Beethoven Quartet, for whom he wrote the work. Just as a short story is said to be more difficult to write than a long novel, a chamber work is also more difficult to perfect than a large orchestral work. Shostakovich certainly believed this - and he should know having written 15 symphonies and the same number of string quartets, dozens of other orchestral works plus numerous other chamber works, solo piano works - for he wrote: "Chamber music demands of a composer the most impeccable technique and depth of thought. I don’t think I will be wrong if I say that composers sometimes hide their poverty-stricken ideas behind the brilliance of orchestral sound. The timbral riches which are at the disposal of the contemporary symphony orchestra are inaccessible to the small chamber ensemble. Thus, to write a chamber work is much harder than to write an orchestral one." The quintet was seen as a reflection of the last, fading glimmer of light in a sea of darkness, coming after the famine caused by collectivisation, the show trials of the late thirties, and before the war that, by now, the people realised was inevitable. In his book Not by music alone Rostislav Dubinsky, first violinist of the Borodin Quartet, recalled that the quintet was even discussed in trams. People attempted to sing the defiant theme from the finale as a kind of personal statement of resistance to it all. It even eclipsed the main football teams’ performances as a topic of conversation for a time - try to imagine that happening on public transport anywhere else! I find this quintet about as perfect as it could possibly be; it has everything: extreme sadness, resignation, lightness and humour and defiance. Few, if any other composers, were able to mirror a people’s feelings more accurately than Shostakovich and thus communicate a collective expression. Socialist realism was supposed to “speak to all the people” which Shostakovich certainly managed to do but often in a way the authorities never meant – small wonder he had his suitcase packed and was ever ready to be carted off to the gulag! Once again Argerich and friends turn in a wonderful performance that emphasises all the above-mentioned qualities. As a child I remember telling my mother I didn’t like chamber music to which she replied that it was an acquired taste she hoped I would one day acquire. Well, I certainly did and it opened up a deeply satisfying world. I would say that those who are either unsure of chamber music or of Shostakovich to start with this work, for if music means anything to them at all this work will speak to them in the most direct of ways. The work opens with a Bach-sounding prelude on piano seemingly foreshadowing his later 24 Preludes and Fugues, op.87, in which he would pay tribute to JS. The quartet then joins in and a typically sombre mood is established. The ensuing fugue continues the mood in which a brooding lyricism is perfectly expressed. The scherzo is presented as a counter to that mood and is full of Shostakovich’s wonderful sense of bizarre irony. This is often a feature of his works in which he establishes a sad plateau after which a cheeky, witty and ironic interlude seems to say “but we can still have some fun even it has to be privately enjoyed”. It’s followed by a restatement of the serious world shared by all but finishes off with a defiant outcry that says “don’t worry, we will win in the end no matter what!”. Indeed in the quintet any joy expressed in the scherzo is soon counterpoised by the intermezzo in which feelings of sadness and regret are perfectly expressed by violins and piano in an almost funereal sounding introduction. This is followed by the two remaining instruments that enter to help emphasise and underline the mood. The finale begins by banishing those blue moods with a light and merry little tune that is a defiant riposte to what went before. This is the section that Dubinsky remembers as being hummed by ordinary people to whom this composer’s works meant so much in those dark days. The quintet ends in a mood of fanciful whimsy to leave the listener with the feeling that all is not lost; in my mind’s eye I see Stan Laurel with his emphatic downward head movement when he’s got one over Hardy. The other Shostakovich work on the disc is his piano trio which he wrote in 1944 in response to the death of his closest friend Ivan Sollertinsky about whom he wrote: "It is impossible to express in words all the grief that engulfed me on hearing the news about Ivan Ivanovich’s death. Ivan Ivanovich was my very closest and dearest friend. I am indebted to him for all my growth. To live without him will be unbearably difficult". He later said that whenever he wrote anything afterwards he would always ask himself what Sollertinsky would have said about it. There is little doubt he would have approved of this work which, once again, is a perfect construct. Argerich is joined by Gautier Capuçon and no less a violin great than the brilliant Maxim Vengerov; the three produce a performance of true quality. The reflective, elegiac first movement gives way to a wickedly biting scherzo full of Shostakovich’s characteristic sardonic wit. The third movement is even more sombre than the first but absolutely beautiful as well as heart-rending. The finale begins once again as a cheeky little dance with Jewish folk overtones. It is subjected to improvisation before the mood becomes serious once again with themes from the previous movements being brought back. The piano suddenly and in a chaconne-like fashion, calls the rest to order. Against this the violin, followed by the cello repeat the cheeky dance slowly and in the most otherworldly way - it speaks as if from another sphere. The trio finishes in a satisfying and reassuring way, putting the grotesque nature behind it. At the time it was written Shostakovich wrote a lot of works which incorporated Jewish melodies. In a way he was using the plight of Jews as a metaphor for the whole of the Russian people and warning them that anti-Semitism is the thin edge of the wedge. I am minded of the declaration by Pastor Martin Niemöller when he said: “First they came for the communists, and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a communist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a Jew. Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak out for me.” The more one listens to both the trio and the quintet the more one can see the justification of Shostakovich’s point about how hard it is to write a successful chamber work. He seemed to be able to produce, with apparent relative ease, works that plumb depths of emotion and almost seem to sum up the human condition, with its inclusion of serious declarations, its satirical and bitter wit and humour, its defiance, as well as menacing statements representing the oppressive nature of the State. These facts are surely proof of his genius. The disc is completed by Jan à ?ek’s Concertino, written in 1925 but sounding considerably more modern. It has an interesting structure in that the first movement is for piano and horn alone whilst the second is for clarinet and piano only. In the two remaining movements those three instruments are joined by two violins, viola and bassoon. It is as delightful a work as it is unusual. Janà?ek had originally intended it to be called “Spring” and there is certainly much about it that is spring like. It has charm, inventiveness, lovely themes, an unusual set of instruments and is lovingly played; what more could anyone ask! Finally we arrive at the final disc in the set which returns to the music of Schumann beginning with the Piano Quintet in E flat in a superb performance – just listen to the scherzo to hear a group of musicians having the best fun which communicates itself to the listener in the most exciting way. This is a sunny work full of exuberance and it is hard to imagine it played better than it is here. Dora Schwarzberg, the violinist on that recording joins Martha Argerich in the next work, the Violin Sonata No.2 in which we are in more familiar Schumann territory. Dora Schwarzberg and Martha Argerich have been playing together for many years and it certainly shows here with the pair communicating as a true duo, each reacting to the other and creating an exciting musical experience. This, together with Argerich’s fabulous pianism and Schwarzberg’s gorgeously rich and sonorous violin playing, showcases this sonata in the best possible light. The lucky people at the concert in Holland where this disc was recorded had the treat of hearing both these works on the same programme plus the very last work on this marvellous set, Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, op.73, this time in its original version for cello and piano with Natalia Gutman as cellist. While I really liked the successful version for flügelhorn from disc 3, there is no doubt when you hear the original that the cello is the perfect vehicle for this wonderful piece. Gutman is a brilliant cellist who was taught, amongst others by Rostropovich. Her mellow tone is lush and the whole piece comes alive in a performance to cherish. So we come to the end of a set designed to celebrate Argerich’s 70 th birthday in which the record-buying public are the beneficiaries. This wonderfully rich and varied programme of fabulous performances of some of the greatest chamber works ever written are offered at a special price considerably less than the cost of any two of the discs taken separately. This is a set that no chamber music lover should be without. If you are an Argerich fan as well and you don’t own these discs already you should not hesitate a moment longer before adding them to your collection. -- Steve Arloff, MusicWeb International Works on This Recording 1. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major, M 8 by César Franck ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano), Itzhak Perlman (Violin) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1886; France ■ Date of Recording: 07/30/1998 ■ Venue: Live Saratoga Performing Arts Center, USA ■ Length: 25 Minutes 46 Secs. 2. Sonata for Violin and Piano no 9 in A major, Op. 47 "Kreutzer" by Ludwig van Beethoven ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano), Itzhak Perlman (Violin) ■ Period: Classical ■ Written: 1802-1803; Vienna, Austria ■ Date of Recording: 07/30/1998 ■ Venue: Live Saratoga Performing Arts Center, USA ■ Length: 34 Minutes 11 Secs. 3. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A major, M 8 by César Franck ■ Performer: Mischa Maisky (Cello), Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1886; France ■ Date of Recording: 12/1981 ■ Venue: Conservatoire, Geneva, Switzerland ■ Length: 28 Minutes 23 Secs. 4. Sonata for Cello and Piano by Claude Debussy ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano), Mischa Maisky (Cello) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1915; France ■ Date of Recording: 12/1981 ■ Venue: Conservatoire, Geneva, Switzerland ■ Length: 11 Minutes 7 Secs. 5. Préludes, Book 1: no 12, Minstrels by Claude Debussy ■ Performer: Mischa Maisky (Cello), Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1910; France ■ Date of Recording: 12/1981 ■ Venue: Conservtaoire, Geneva, Switzeralnd ■ Length: 2 Minutes 21 Secs. 6. La plus que lente by Claude Debussy ■ Performer: Mischa Maisky (Cello), Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1910; France ■ Date of Recording: 12/1981 ■ Venue: Conservatoire, Geneva, Switzerland ■ Length: 4 Minutes 32 Secs. 7. Quintet for Piano and Strings in E flat major, Op. 44 by Robert Schumann ■ Performer: Mischa Maisky (Cello), Lucia Hall (Violin), Nobuko Imai (Viola), Martha Argerich (Piano), Dora Schwarzberg (Violin) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1842; Germany ■ Date of Recording: 09/18/1994 ■ Venue: Live Concertgebouw, Nijmegen, Holland ■ Length: 29 Minutes 58 Secs. 8. Andante and Variations for 2 Pianos, 2 Cellos and Horn in B flat major, Op. 46 by Robert Schumann ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano), Mischa Maisky (Cello), Alexandre Rabinovitch (Piano), Natalia Gutman (Cello), Marie-Luise Neunecker (French Horn) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1843; Germany ■ Date of Recording: 09/18/1994 ■ Venue: Live Concertgebouw, Nijmegen, Holland ■ Length: 18 Minutes 37 Secs. 9. Phantasiestücke (3) for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 73 by Robert Schumann ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano), Natalia Gutman (Cello) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1849; Germany ■ Date of Recording: 09/18/1994 ■ Venue: Live Concertgebouw, Nijmegen, Holland ■ Length: 9 Minutes 55 Secs. 10. Märchenbilder for Viola and Piano, Op. 113 by Robert Schumann ■ Performer: Nobuko Imai (Viola), Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1851; Germany ■ Date of Recording: 09/18/1994 ■ Venue: Live Concertgebouw, Nijmegen, Holland ■ Length: 15 Minutes 54 Secs. 11. Concertino for Piano, 2 Violins, Viola, Clarinet, Horn and Bassoon by Leos Janácek ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1925; Brno, Czech Republic 12. Trio for Piano and Strings no 2 in E minor, Op. 67 by Dmitri Shostakovich ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1944; USSR 13. Contrasts for Violin, Clarinet and Piano, Sz 111 by Béla Bartók ■ Performer: Chantal Juillet (Violin), Martha Argerich (Piano), Michael Collins (Clarinet) ■ Period: 20th Century ■ Written: 1938; Budapest, Hungary 14. Trio for Piano, Violin and Cello in G major, H 15 no 25: 3rd movement, Rondo all'Ongarese "Presto" by Franz Joseph Haydn ■ Performer: Martha Argerich (Piano) ■ Period: Classical ■ Written: 1795; London, England 15. Trio for Piano and Strings no 1 in D minor, Op. 49 by Felix Mendelssohn ■ Performer: Gautier Capuçon (Cello), Martha Argerich (Piano), Renaud Capuçon (Violin) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1839; Germany 16. Introduction and Polonaise for Cello and Piano in C major, Op. 3 by Frédéric Chopin ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1829-1830; Poland