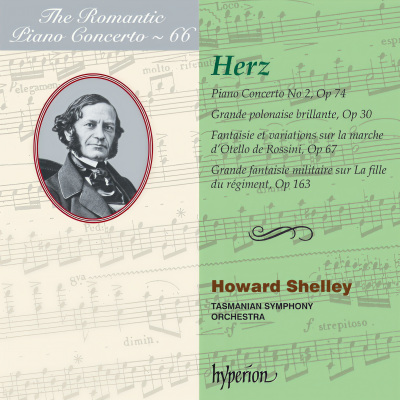

Herz: Piano Concerto No. 2 & Other Works (Hyperion Romantic Piano Concerto 66)

Henri Herz—as much a phenomenon in 1830s Paris and for the ensuing decades in America as he has been derided since the curtain fell on his world of sparkle—wrote eight piano concertos. One is lost, so it is for the final time in this mini series that Howard Shelley and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra here get to put on their finest dancing shoes and perform the Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor (the one with which Herz conquered America in 1846) and three extended fantasies. * * * If he is included at all, most reference works routinely dismiss Henri Herz as a superficial nonentity whose oblivion as a composer is well deserved. While admitting that he was a remarkably dexterous pianist, none of his works—and they exceed 200 in number—is, apparently, worth a bag of beans. Out of print for well over a century and with no performances, one wonders how Herz’s music came to be judged. The suspicion is that the opinions we have come to rely on are second- or third-hand, derived from nineteenth-century commentators with a different musical aesthetic to our own. Today we live in an age which is keen to investigate the forgotten music of the past, we have access once again to so many long-lost scores, and we are free from the German hegemony that for so long prescribed musical taste and standards. The six of Herz’s total of eight piano concertos previously recorded by Howard Shelley offer ample evidence of an imaginative composer with a unique voice. Born Heinrich Herz in Vienna on 6 January 1803 (some sources say 1806), he studied at the Paris Conservatoire from 1816 where, in his first year, he carried off first prize for piano playing. Having become a thorough Parisian, Heinrich became Henri and the French capital remained his base for the rest of his life. From here he conducted an industriously creative and successful career as a pianist, composer, teacher, inventor and piano manufacturer. Herz the pianist might have reminded Mendelssohn of ‘ropes and acrobats’ but his compositions became so popular that for twelve years until the late 1830s he outsold all his contemporaries. He became a professor at the Conservatory in 1841, a post he held until 1874, and joined in a Parisian piano making business. In 1844 his factory produced 400 pianos a year and employed more than 100 workmen, yet by the mid-1840s it seems extra capital was needed. Whether the chief motivation was music or money is uncertain, but in 1846 Herz took up an invitation to visit the United States, the first pianist of any importance to do so. John Sullivan Dwight (1813–1893), America’s first influential music critic, was left entranced: It seems almost impossible to conceive of anything more perfect than Herz’s mastery of his instrument. His touch so delicate, precise, and forcible, individualizing every note … his running passages so smooth and even, that a gentle breeze playing over the bending surface of a field of grain could not announce its presence by a more sure and uniform and quiet display of power … and the accomplishment of all this with less show of exertion than it costs an ordinary player to perform an easy piece. Such was Herz’s success that he remained in the States until 1851, travelling as far as California and the West Indies, returning to Paris a wealthy man. He died in 1888, the same year as Alkan, the year of Mahler’s First Symphony, Franck’s Symphony in D minor and Richard Strauss’s Don Juan. The time for Herz’s style of music had passed but, as the present recording illustrates, that does not mean that ipso facto it is music without merit. For a more detailed account of Herz’s life and career, please see Volume 35 in Hyperion’s Romantic Piano Concerto Series (CDA67465). Herz’s Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor, Op 74, composed around 1830, was still very much in his repertoire when he first arrived in America. He played it for his debut there (New York, 29 October 1846). So captivated was the audience by the Rondo that it was repeatedly interrupted with bursts of applause. ‘A composition of rare merit’ was the verdict of the New York Evening Mirror while the Morning Courier praised its orchestration and ‘beautiful chaste’ style, finding that it was not ‘one of those flimsy combinations—called concertos by some modern performers—composed of rapid airs with humdrum accompaniments and unmeaning cadenzas, and which might as well be played commencing in the middle of the road or the end, as at the beginning’. The dotted figure of the concerto’s initial theme (Allegro moderato) and the ingratiating second subject, both announced by the orchestra, are not immediately taken up by the soloist; the piano’s vigorous entry derives from the repeated triplet/quaver figure first heard played by the strings and then adopted by the hushed timpani. Continuing with a fourth theme (another lyrical idea) and a reference to the first subject, it is only after an extended cadenza-like flourish that the piano returns to the second subject (5'13''). This sends it dancing on its merry way in the relative key of E flat major, a non-stop succession of keyboard acrobatics, before a tutti which, using the triplet/quaver figure, brings the movement to a conclusion with a resounding C major flourish. The theme of the brief second movement (Andantino cantabile con molt’ espressione), which Herz sets in the key of E major, is a hushed reverie of great beauty, one that might pass for a lullaby or a plaintive Scottish folk song. The two horns, trombones and timpani used extensively in the first movement are dispensed with. After an impassioned central section, the melody returns highly decorated by the piano (many delicate runs to the top of the keyboard) before the woodwinds take up the tune underpinned by the soloist’s sotto voce filigree passagework. The Rondo (Allegro vivo, 3/8 in C major) follows attacca and begins innocently enough, after a teasingly hesitant introduction, with the catchy theme—in fact a stream of themes—that so delighted Herz’s American audiences. A second, minuet-like idea is announced by the oboes and horns, a third by a tutti at 1'52''. They must have marvelled at Herz’s rapid leggiero skitterings, a daunting semiquaver passage in leaping tenths and twelfths, a brilliant repeated-note variation, and the bravura sprint to the end. Herz, after his first performance of this in America, refused to encore the movement despite the enthusiastic requests. One could hardly blame him. Herz’s Grande fantaisie militaire sur La fille du régiment, Op 163, was published around 1850. Donizetti’s comic opera was an instant success when it was first produced in 1840 (it ran to fifty performances). Once described as ‘the best French opera ever written by a non-Frenchman’, probably its best-known number is ‘Chacun le sait, chacun le dit’ (‘All men confess it, go where we will’), otherwise known as the ‘Song of the regiment’ which the eponymous daughter Marie sings in Act 1 (it is briefly referred to in the overture). After an Andante maestoso introduction and a flowery cadenza, Herz introduces the theme and, linked by militaristic orchestral tuttis, offers two sparkling variations. The key changes from F major to D flat major for a brief Adagio passage marked A cappricio [sic], which leads to an expressive Andante cantabile melody first heard in the introduction. Reverting to F major and a further two variations in 3/8, there is a brief reflection before the metre changes to 2/4 for a spirited gallop to the end. Herz follows much the same procedure in the Fantaisie et variations sur la marche d’Otello de Rossini, Op 67, published in 1832. Rossini’s opera, though rarely performed nowadays, was enormously popular throughout the nineteenth century until being eclipsed by Verdi’s masterpiece, not least because Rossini’s version presents such a travesty of Shakespeare’s original. Nevertheless, this Otello, first performed in 1816, contains much fine music including the dapper march from early in Act 1 that Herz uses as the basis of this Fantaisie. The ornate Andante maestoso introduction is succeeded by a cadenza of fast repeated notes which would surely have tested the action of the pianos of that era. (Some eight years after his Op 67 appeared, Herz patented a simplification of Erard’s double escapement action, the model for today’s grand pianos, which would have made the execution of such a passage more efficient.) The march’s simple two-part structure is applied to the two variations that follow its initial statement, the second of these in con velocità triplets. Herz then modulates from the tonic of C major into E flat major for the central Andante con molt’ espressione section in 12/8. This leads to an elaborate cadenza which modulates into a brief, animated excursion in E major, marked Tempo di marcia, before a return to the tonic for the finale. Perhaps inevitably, the pianist is presented with more machine-gun repeated notes, cruel semiquaver tenths and demisemiquaver runs in thirds (con molta forza), all played in the spirit of a typical Rossini crescendo. The Grande polonaise brillante, Op 30, is the earliest work on this recording, published in 1827. This is intriguing, since to many ears there are a number of passages, not least the main theme of the polonaise, that sound distinctly Chopinesque (the only piece here which could be so described). Yet the Polish composer, Herz’s junior by only seven years, did not compose his popular Grande polonaise, Op 22, until 1830, shortly before arriving on Herz’s Parisian home patch in mid-September 1831 (the Andante spianato which precedes Chopin’s work was not added until 1834). Coincidence, serendipity or simply the inevitable result of cross-fertilization? On the other hand, Ignaz Moscheles, who befriended Herz in 1821 and whose style had a profound influence on the younger man, had composed several years earlier a Polonaise précédée d’une Introduction pour piano, Op 19. We can only speculate as to who heard what and when, and whether any of the works influenced the others. Herz’s Grande polonaise, typical of the scintillating crowd-pleasing Parisian style of the day, deserves a place in the repertoire just as much as Chopin’s—and it could achieve that if only more artists, concert promoters and audiences looked beyond the ‘brand names’ of nineteenth-century piano music. Jeremy Nicholas © 2015