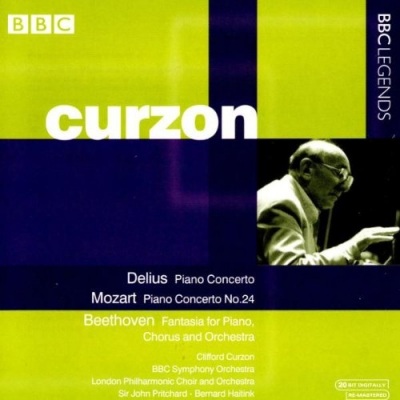

Delius: Piano Concerto / Mozart: Piano Concerto No.24 / Beethoven: Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Or

One of the most invaluable features of the BBC Legends series is that it often allows us to hear live performances by artists in repertoire that they did not record commercially. This is the case in one, and possibly two of the items included on this disc. Sir Clifford Curzon (1907-1982) was not only a very great pianist but also a famously fastidious one. I vividly recall a performance by him of the Brahms D minor concerto with James Loughran and the Hallé Orchestra in Bradford nearly thirty years ago when he stopped the performance not long after his opening entry in the first movement because there was a fault with the action of one of the piano keys. His tremendously self-critical nature and increasing reluctance to preserve a performance through recording lest fallibilities be exposed meant that his discography is frustratingly small for an artist of his stature. I’m not aware that he recorded either the Delius concerto or the Beethoven Fantasia commercially, which makes this release so valuable to his admirers. The Mozart concerto is in his discography. He made a justly celebrated recording of it for Decca in 1968 with the LSO and Kertész. The present live performance with Haitink is also a fine one. It’s suitably, but not excessively, muscular in the opening movement. Right from the start Haitink presents a strongly profiled account of the orchestral introduction and here, as will be the case throughout the reading, there’s some excellent playing from the LPO woodwind. In the hands of Curzon and Haitink the music seems to unfold seamlessly and inevitably. Curzon turns every phrase beautifully. He manages to make everything sound spontaneous but you know that, in fact, everything he does has been very carefully considered. This is one of Mozart’s darkest concerto movements and Curzon gives a performance that is powerful but in which the power is never overdone and is not at the expense of style. In all this he’s helped enormously by having such a committed and supportive accompanist as Haitink. There’s grace and poise in the slow movement. Again, besides Curzon’s marvellously stylish and thoughtful pianism, there are some fine contributions from the woodwind section of the LPO. The finale is nicely pointed and features incisive playing from Curzon. I must admit that I’ve heard more playful accounts of the compound time final pages but Curzon’s serious-sounding approach here is not a drawback. In summary this is a fine, authoritative reading of the concerto and it’s a valuable supplement to Curzon’s studio account. The Beethoven Fantasia is a curious, hybrid work. It contains elements of concerto style and also, at the end, sounds like a small dry run for the finale of the Ninth symphony. Composed in 1808 it comes between the Fourth and Fifth Piano concertos and is contemporaneous with the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies. It was first heard at a concert in Vienna in December 1808. On that occasion the audience heard also the premières of those two symphonies and, for good measure, the aria Ah, perfido as well as movements from the Mass in C major. What a marathon! In brief, the work opens with a lengthy piano cadenza, which lasts until 3:36 in this performance. Curzon is commanding here. Then the orchestra joins in, the main theme of the movement is announced and soloist and orchestra play a series of variations on it. It is not until near the end that the chorus makes their contribution (15:46 here). The performance is decent enough though I’m not convinced that Haitink is on such fine form as was the case in the Mozart – but then the Mozart is a much greater work. The vocal contribution is adequate – one is conscious how much choral standards have risen in just the last three decades or so. At the start of the choral section Beethoven calls for a quartet of soloists. Usually in performances I’ve heard or taken part in this section is sung by a semi-chorus of say two to a part. The ensemble sounds a little bigger than that here – perhaps four to a part? The trouble with this performance is the sound quality. I don’t know what is the source of the recording but I’m sorry to say the sound is some of the worst I’ve heard from this label. The piano sound is clangy and whenever the dynamics are loud the sound crumbles and is poorly focused. To be honest, I’ve heard on CD much better reproduction of radio broadcasts that are twenty or more years older than this. This, really, is a recording only for Curzon completists, though I don’t dismiss its usefulness if, as I think is the case, there’s no commercial recording of the work by him. The Delius concerto is a genuine rarity, not just in terms of Curzon’s legacy but also because performances of the work itself are fairly infrequent. The work had its origins in an early Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra, composed in 1897. It was then substantially revised into a three-movement form in 1904 (see review of a recording by Piers Lane) before a further revision in 1907 left the work in the form that’s best known these days and in which the work plays without a break. Curzon plays the version from 1907 – coincidentally the year he was born – and he plays it with evident enthusiasm. As Bryce Morrison puts it in his notes, Curzon is “ clearly in love with its meandering, Grieg-inspired rhetoric.” In fact I think that phrase is an excellent summary of the concerto. The red-blooded, romantic passages, in which the heart is very much worn on the sleeve, may surprise some listeners. Right from the start this note is struck in a big, confident, sweeping opening, which Curzon plays for all it’s worth. The support from Pritchard and the BBC Symphony Orchestra is similarly impassioned. However, it’s not long before Delius is off down one of his “meandering” stretches (2:11 – 3:50) and Curzon judges the reflective mood unerringly. But for much of the movement the mood is bold and striking, as in the passage containing huge piano chords from around 7:13. The second movement, which takes over at 11:11, starts as a dreamy idyll. Curzon and Pritchard are good in this ruminative section. Gradually the music builds to a climax in which the horns are to the fore before the pensive mood of the opening is restored. The final section (from around 19:00) is linked to the previous movement by a piano cadenza. Much of this closing section is red-blooded romantic stuff but Delius can’t resist inserting some reflective musings and they’re presented very well here, a good example being the beautiful, quietly singing passage with a solo violin joining the piano (around 22:00). This is not one of the composer’s finest works but it’s good to hear a master pianist giving such a fine account. In his notes Bryce Morrison reminds us that in his early career Curzon had a very wide concerto repertoire but I wonder how often he played this Delius work – it would be fascinating to know. I assume from the date and venue of the performance that it was given at the Promenade Concerts. It is accorded a Proms-style ovation. Despite the sonic limitations of the Beethoven work this is a valuable and most interesting release. Bryce Morrison quotes Curzon thus: “You see, the joy of a performance is that it disappears like an imprint on water, lost for ever.” Well, thanks to BBC Legends these performances have not been lost for ever and Curzon’s many admirers will be profoundly grateful for that. -- John Quinn, musicweb-international.com