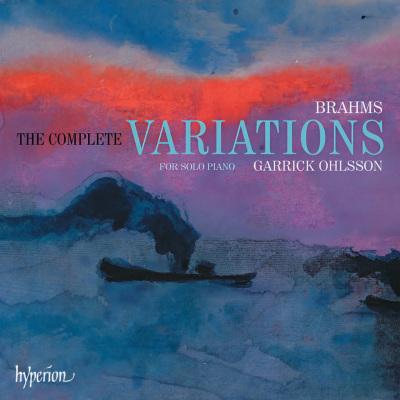

Brahms: Complete Variations for Solo Piano

Garrick Ohlsson专辑介绍:American pianist Garrick Ohlsson, whose Complete Chopin set was acclaimed as one of the most important anniversary releases of 2010, now turns to another significant, though often overlooked, body of Romantic piano music—Brahms’ complete variations. The coruscatingly difficult Paganini variations, a bravura display of pyrotechnic virtuosity, frequently feature in piano competitions, performed to demonstrate extraordinary technique. In this performance, Garrick Ohlsson also displays remarkable musicality. The Variations and Fugue on a theme of Handel is one of the summits of his entire keyboard output, showing the composer at the height of his powers. This 2-disc set also contains some little-known gems, including the wonderful Variations on an Original Theme. In the years following the composition of his three sonatas in 1851–4, Brahms concentrated his piano output on sets of variations and groups of shorter pieces—and the first representatives of those genres are already powerful indications of his mastery in these smaller forms. The art of variation was one that he had absorbed very early, partly perhaps from his piano teacher Eduard Marxsen, who himself composed many works in variation form, and he came to consider himself something of a connoisseur of variation technique. Apart from the brief sets of variations on folksongs which constitute the slow movements of his first two piano sonatas, the earliest (and simplest) of Brahms’s existing sets of piano variations is the Variations on a Hungarian Song, Op 21 No 2, composed in 1853 but only published eight years later. The work is based on a rugged eight-bar melody, rhythmically enlivened by its alternating bars of 3/4 and 4/4, which Brahms probably derived from his Hungarian violinist-friend Ede Reményi during their concert tour together in the spring of that year. There are thirteen variations in all, plus a finale: the obstacle to variation posed by the tune’s rhythmic asymmetry was perhaps what attracted Brahms in the first place. His first eight variations retain its metrical irregularity, and the theme remains throughout as a kind of cantus firmus, though often subtly transformed—as in the ‘gypsy’ colouring of variation 5, whose repeated notes and rhythmic hesitations evoke the sonority of the cimbalom and also (perhaps only from similarity of inspiration) passages in the Hungarian Rhapsodies of Liszt. From the ninth variation onward Brahms standardizes the metre to two beats in the bar, though he keeps the eight-bar structure. However the last variation finally breaks free of these confines and develops into an extended and increasingly brilliant finale at doubled speed. This entails further variations, and culminates in a triumphant restatement of the Hungarian theme. Undeniably attractive, the Variations on a Hungarian Song is merely a work of promise, whereas the deeply elegiac Variations on a theme by Schumann, Op 9 is Brahms’s first true masterpiece in the genre. The almost overwhelming pathos of this work mirrors the circumstances of its composition in proximity to the stricken Schumann household in Düsseldorf in May and June of 1854 (apart from variations 10 and 11, which were inserted in September). Schumann had only recently been confined in the Bonn asylum for the insane, leaving his wife Clara, pregnant with their seventh child, to look after their five surviving children. She is the work’s dedicatee; Brahms brought each of his variations to show her as he composed them. The theme comes from the fourth of Schumann’s Op 99 Bunte Blätter—and is the same theme as Clara, herself an accomplished composer, had chosen for her own set of Variations, Op 20, composed the previous year. But it is Robert Schumann who chiefly presides over Brahms’s work: there are stylistic and textural reminiscences of several of his other works, and the variation techniques as such, based especially on the free melodic transformations of the theme or its bass in ‘fantasy’ style, show Brahms absorbing some of Schumann’s most personal innovations. (In the manuscript, though not as published, many of the individual variations are signed: the more lyrical ones with ‘B’—for Brahms—and the faster, more ardent ones with ‘Kr’—for ‘Johannes Kreisler Junior’, the romantic alter ego Brahms had invented for himself while still a teenager, after the protagonist of E T A Hoffmann’s novel Kater Murr. This is a clear emulation of Schumann’s ascription of different parts of his Davidsbündlertänze to ‘Eusebius’ and ‘Florestan’.) The first four variations adhere to the plaintive theme’s twenty-four-bar outline, and the first eight to its key (F sharp minor); but as the work proceeds Brahms alters tonality and proportion freely. Throughout, he shows great resource in presenting a varied sequence of musical character and mood—though all is tinged with varying gradations of melancholy. Variations 1–7 make up a structural unit. Against the sadness inherent in the theme itself they make progressively more vigorous attempts towards positive activity, climaxed by the passionate Allegro of variation 6—only to be brought short by the numbed stillness of No 7. No 8 then reintroduces the theme in a serenade-like evocation of its original shape, and in the windswept variation 9 the key shifts to B minor, with an allusion to Schumann’s Bunte Blätter No 5, a companion-piece to the one from which the theme derives. The song-like variation 10 (in the manuscript Brahms called it ‘Fragrance of Rose and Heliotrope’) brings a warm shift to D major and at its final cadence quotes the ‘Theme by Clara Wieck’ on which Schumann based his Op 5 Impromptus. The delicate variation 11 is transitional in character, leading to the staccato No 12, the toccata-like 13, and the nocturnal 14, with its close and plangent canon. The penultimate variation is an Adagio in the tonic major (though written as G flat): a long-spanned augmentation of the theme tolls out in canon between treble and bass, sonorous arpeggios spanning the divide like an Aeolian harp. Finally, variation 16 is a very slow, stark, almost skeletal coda, the melody fragmented into poignant chordal sighs, conveying a mood of infinite regret. The Variations on a Hungarian Song were published together with the more extended and sophisticated Variations on an Original Theme, Op 21 No 1. Like its companion, this is certainly an earlier piece than its opus number would suggest, but the exact date has remained elusive. All we know for sure is that it is later than 1854 (and therefore than the Op 9 Schumann Variations), but most probably it dates from the difficult years 1855–7 when Brahms, frustrated with what seemed to him the shortcomings of his compositional technique, turned out a large number of vocal and instrumental pieces which attempted to assimilate the lessons he derived from the study of earlier masters. Op 21 No 1 is a searching and personal creation of considerable poetry and substance, yet it belongs to this general orbit insofar as it investigates and seeks mastery over new aspects of variation-technique. The predominant mood is lyrical yet pensive, and we seem to glimpse the composer communing with himself. The theme is a beautiful melody in D major, presented in a rich contrapuntal setting that leaves it almost over-supplied with possibilities. However, Brahms concentrates on the theme’s harmonic structure to provide a framework for fresh invention—though paradoxically the harmonic structure is itself dominated and somewhat restricted at each end of the theme by a pedal bass, whose implications are sometimes accepted and sometimes ignored. There are eleven variations, and all except the last are confined to the theme’s unusual dimensions: two nine-bar halves, each half repeated. The first seven variations, all in D major, are quiet and introspective, featuring several technical devices that at the time were considered ‘archaic’. No 5, for instance, is a canon in contrary motion, the canon moving a bar closer in the variation’s second half. The bareness and angularity of No 7, an even stricter canon, with its wide leaps for both hands, almost looks like Webern on the page. With No 8, a vigorous study in martial dotted rhythms, the pace increases and the tonality shifts to the minor. The next variation forms the dynamic climax, turning the pedal bass into rumbling drum effects to bolster emphatic chordal writing. From here the music subsides uneasily to variation 11, which returns to D major and to the original tempo of the theme, then opens out into an expansive coda that eventually achieves a subdued but beautiful resolution, with a final reminiscence of the theme in a lulling berceuse-like rhythm. Brahms’s next important example of variation form was not a piano work but a piece of chamber music: the noble slow movement of his String Sextet in B flat major, Op 18. But Clara Schumann, having heard a play-through, begged Brahms for a piano transcription of this movement, and he complied with the Theme and Variations in D minor in time for her birthday on 13 September 1860. Though this piano arrangement remained unpublished until after Brahms’s death, he was very fond of it. The stern, rather archaic theme and the rigid adherence of all the ensuing six variations to the theme’s dimensions, including repeats, suggest a debt to Bach, and especially to his D minor Chaconne for solo violin. But equally these variations so transform the theme, and are so rich in their contrasted sonorities, that they completely transcend the strictness of the form. The most striking inventions are probably the third variation, with its turbulent ebb and flow of rapid scales; the magniloquent fourth, which gives the theme its most impassioned expression in the major; and the sixth, which serves as a spectral coda, the theme returning as a mere shadow of itself. The climax of Brahms’s activities as a composer of piano variations came a year later, with the Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, Op 24. Completed in Hamburg in September 1861 and dedicated to Clara Schumann on her birthday, this is one of the summits of his entire keyboard output, showing him at the height of his powers. It was also—and hardly by coincidence—Brahms’s first major compositional statement following his 1860 ‘Manifesto’ against the composers of Liszt’s ‘New German School’, who were advocating the literary tone-poem and Wagnerian music-drama as the ‘Music of the Future’. Brahms’s Op 24 is a systematic summation of the mastery he had gained through intensive study during the previous decade. The choice of a Baroque theme, the strictness of the variations, the richness and scope of the piano technique, and the lavish display of contrapuntal learning in the concluding Fugue, all combine to present Brahms in the role of preserver and representative of tradition. Even Wagner saw its significance when Brahms played it to him, commenting grandly that it showed what could still be done with the old forms by someone who knew how to use them. The theme is the Air from Handel’s B flat major harpsichord suite, published in 1733 (Brahms, the passionate bibliophile, owned a first edition). This dapper little tune has the balanced phraseology, the structural and harmonic simplicity, of an ideal variation subject. Brahms’s twenty-five variations confine themselves to the key of B flat, with occasional excursions into the tonic minor. But this apparent constraint, while imposing a powerful structural unity, provides Brahms with a framework on which to establish and explore a kaleidoscopic range of moods and characters. Several of the variations form pairs, the second intensifying and developing the characteristics of the first, while the last three create a climactic introduction to the concluding Fugue, on a subject derived from Handel’s theme. This continues the variation process in an altogether more ‘open’ form in which Brahms reconciles the linear demands of fugal form with the harmonic capabilities of the contemporary piano. The grand sweep of the structure, however, is never lost sight of, and the Fugue issues in a coda of granitic splendour. Given that the Handel Variations is such a musical manifesto for traditional values in composition, it is surprising that Brahms’s next variation-work, on the most famous of all themes by Paganini, should prove to be a bravura display of pyrotechnic virtuosity, as practised by the keyboard lions of the ‘New German School’. Liszt (whose compositional principles and powers Brahms profoundly distrusted) was the prime exponent of that style; but among those next in rank was one of Liszt’s favourite young pupils, Carl Tausig (1841–1871), whom Brahms first met in Vienna during the winter of 1862–3. They became good friends, played together as duet-partners and in 1864 gave the first public performance of Brahms’s Sonata for Two Pianos Op 34b. It was to Tausig that Brahms now dedicated his two books of Variations on a theme by Paganini, Op 35—as if to demonstrate that he was as much a master of the new style of piano-writing as of the old. Brahms’s friends often referred to the result as the Hexenvariationen (Witchcraft Variations). ‘Variations on a theme by Paganini’ is in fact only Op 35’s subtitle. The main title, as if to emphasize its exploration of the technical aspects of keyboard virtuosity, is Studien für Pianoforte; and Brahms organized it in two complementary books, each of which contains the theme (from Paganini’s famous Caprice No 24 in A minor for solo violin), plus fourteen variations and a coda. The choice of theme is itself a direct challenge to Liszt, who had produced his own virtuoso recomposition of this Caprice in his Grandes études de Paganini (1838, revised 1851). Since Brahms’s time, many other composers have done their best or worst in variations on this theme, among them Rachmaninov, Lutoslawski, Boris Blacher and Andrew Lloyd Webber. The simplicity and clarity of the theme’s harmonic skeleton seems to afford each new composer almost unlimited scope for the imposition of his own personality. Brahms’s variations open up a whole world of interpretative challenges, and take technical problems as the point of departure for expressive recreation. They include studies in double sixths, double thirds, huge leaps between the hands or with one hand. There are trills at the top of wide-spread chords, polyrhythms between the parts, octave studies, octave tremolos. Other variations explore staccato accompaniments against legato phrasing, glissandi, rapid contrary motion, and swooping arpeggios against held notes. During many of the variations the figuration is systematically transferred from right hand to left, and vice-versa. Not that each variation confines itself to one technical feature; several may be combined and in both books the final variation is welded to an extended three-part coda, covering an even larger range of difficult techniques and bringing each book to an end in scintillating style. Generally speaking, in Book I the focus is on bravura writing. Technical demands occupy the music’s foreground, leaving scant space for Brahms’s habitual melodic developments; nevertheless, the delicate arabesques of the major-key variation 12, and the Hungarian accents of No 13, with its ‘gypsy’ glissandi, are delightful. Book II is somewhat gentler in character, with compositional virtues more predominant. The dreamy waltz of variation 4, the skittish arpeggios of No 6 with its ‘demonic’ crushed semitones, the ‘violinistic’ No 8 with its pizzicato effects, the cool nocturne of No 12 (the only variation in either book that strays from the orbit of A minor/major, into F), and the gently cascading thirds of No 13—these all combine to make Book II the more satisfying from a purely musical standpoint. Taken as a whole, however, the Paganini Variations is a stunning demonstration of Brahms’s compositional skills. Calum MacDonald © 2010